Do I need a DNR?

A few months ago, I wrapped up an estate planning meeting with a woman who has been my client for many years. Her life had changed, and we revised her will, revocable trust, and powers of attorney for property and health care. We also updated her personal Declaration of Intent, in which she detailed her wishes about life sustaining treatments and her end-of-life care. As she left the office, one more question came to her “Do I need a DNR?”

A few months ago, I wrapped up an estate planning meeting with a woman who has been my client for many years. Her life had changed, and we revised her will, revocable trust, and powers of attorney for property and health care. We also updated her personal Declaration of Intent, in which she detailed her wishes about life sustaining treatments and her end-of-life care. As she left the office, one more question came to her “Do I need a DNR?”Like most legal issues, the answer to the question is “It depends.”

A few definitions

Before discussing the question, a few definitions are needed.

DNR stands for “Do Not Resuscitate.” A DNR order is a hybrid medical order and advance directive about emergency care, specifically CPR.

CPR stands for “Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation.” CPR is a medical procedure that attempts to restart your heartbeat and breathing if your heart stops (cardiac arrest). It’s the procedure that you’ve seen numerous times on television.

CPR usually starts with chest compressions to imitate a heart beat and keep blood flowing to the brain. If the chest compressions do not start a heartbeat, they are typically followed by electrical shocks to the heart, intravenous medicines, and the insertion of a breathing tube.

In Illinois, a DNR order is a direction, a medical order, to emergency medical personnel instructing them not to perform CPR, if the patient is found in cardiac arrest. In other words, if the paramedics are called and find that the patient has died (no heartbeat or breathing), they are not to attempt any heroic measures to resuscitate (CPR) the patient, and bring him or her back to life. A DNR order is a direction to the paramedics to allow the patient to have a natural death.

Who is likely to have a DNR?

A DNR is typically completed by someone who is likely in the last year of one’s life. A DNR is appropriate for one who is frail, elderly, with a limited life expectancy, and who has a medical condition that is destroying one’s quality of life, without the likelihood of getting better.

A DNR is also appropriate for one who may lose the capacity to make one’s medical decisions within the next year, such as persons living with dementia.

A DNR may act as advance statement of the person’s wishes, a statement made while the person can still communicate one’s wishes.

A third category includes persons who have strong opinions about end-of-life treatments, such as those who are ready to accept death and are ready to allow a natural death to occur.

Why would one want a DNR?

It seems like an odd question. Why wouldn’t a person want CPR? Why wouldn’t a person want their life to be saved and their heart restarted?

Most people have not had a first-hand experience with CPR; they’ve never seen CPR performed on a loved one or acquantance. Most people’s view of CPR is based on what they’ve seen on television. Unfortunately, the medical shows have created an unrealistic expectation of CPR.

On television, it seems like CPR saves almost everyone. In real life, however, the results are much different.

On television, about 75% survive. It’s usually an all-or-nothing result. The character either survives, with no resulting issues, or the character dies. Overall, CPR is a good thing.

In real life, the results are much different. The actual survival rate is about 10 to 15%. Most of those that survive have serious physical injuries or mental deficiencies from the CPR. These problems are on top of whatever health issues caused the person’s heart to stop in the first place.

There are, of course, many factors that influence the survival rates of those who have CPR. The younger the person, the better. The healthier the person, the better. Getting CPR in the hospital is better than getting it at home.

If you are elderly, sickly and home-bound, the chances of surviving after CPR are greatly reduced. In Whatcom County, Washington (which includes Bellingham), during 2013 and 2014, not one patient who received CPR in a nursing home survived.

CPR can be violent

The first attempts at CPR usually involve chest compressions. The image that comes to mind is that of a paramedic leaning over a patient’s chest, pushing on the chest to imitate a heartbeat and breathing. But real CPR isn’t a simple pushing on the patient’s chest for a couple minutes, as is typically seen on television.

In order to be effective, it is recommended that the chest be compressed 2 inches at a rate of 100 times a minute! A two-inch compression means that your chest is being compressed about the thickness of your hard-bound high school dictionary. A 100 times a minute is more than 1-1/2 compressions per second.

In five minutes of CPR, your chest will have been forcefully compressed 500 times.

Over 75% will have physical injuries from CPR. These injuries can include multiple broken ribs, broken breastbone, damage to the lungs and internal organs, and internal bleeding. Many who survive CPR end up in an intensive care unit on a ventilator, while these new injuries are addressed.

Brain damage likely

CPR is performed when one’s heart stops beating. When one’s heart stops, the brain is deprived of oxygen. In seconds, without oxygen, the brain begins to shut down. In minutes, permanent brain damage can occur.

Even if CPR is successful (your heart is restarted), if the start of CPR was delayed, the lack of oxygen to the brain may result in long-term disability. Functional deficits can include memory loss, speech issues, partial paralysis, reduction of attention span, and the inability to get things done or perform tasks.

Even if CPR is successful, about one-half will have serious brain damage, and approximately 10% will remain in an irreversible coma.

Dr. Jessica Zitter, an ICU doctor, has an even more critical view, stating that “[CPR] is rarely successful. Very few patients ever leave the hospital afterward. Those that do rarely wake up again.”

Why do I need a DNR?

Before most medical procedures are performed, the doctor or hospital needs to explain the procedure to us, discuss the pros and cons with us, and get our “informed consent.” Nothing can be done to us, unless we agree, unless we “opt-in” ahead of time.

CPR is one of the few medical procedures that we don’t get to “opt-in.” Because of the emergency situation, our consent to CPR is presumed. The paramedics are legally obligated to use all available life-sustaining treatments, absent a medical order to the contrary.

The reason why you might need a DNR is because a DNR order is the only way that you can “opt-out” of CPR, if your heart has stopped. It is a medical order that directs paramedics to allow you to die naturally, and permits the paramedics to legally stop their interventions.

Note: Paramedics can only rely on medical orders. A Power of Attorney for Health Care is NOT a medical order, it is an advance directive. The agent under your POA for Health Care has limited authority in a emergency. If you do not have a DNR, the paramedics will not act upon your agent’s direction in an emergency situation, even if your agent tells the paramedics that you did not want CPR.

What does a DNR look like?

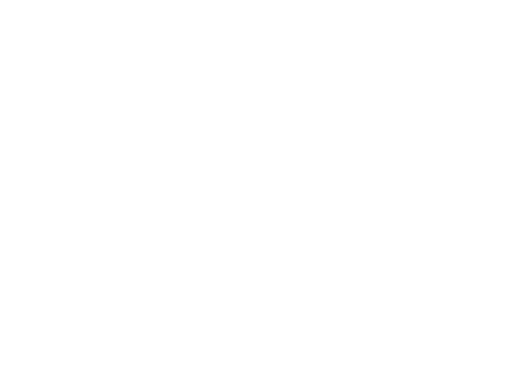

Several years ago, the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) published an approved DNR form. It has been revised and the DNR form is now part of the IDPH Uniform Practitioner Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Form. There is no longer an approved free-standing DNR form.

The DNR is now set forth in Section A of the POLST. The form is quite simple and straight-forward. If you do not want CPR when your pulse and breathing have stopped, you simply check the “Do Not Attempt Resuscitation/DNR” box in Section A. It is interesting to note that you also have the option to require that CPR be performed.

The remainder of the POLST allows you to choose options relating to end-of-life issues, including Medical Interventions (life-sustaining treatments) and Medically Administered Nutrition (e.g., feeding tubes).

The POLST (including the DNR in Section A) is medical order. A medical order involves the concept of informed consent. The POLST and DNR must be completed as part of a discussion between you and your doctor (or other authorized medical practitioner) about your situation and your wishes.

The 2016 IDPH Uniform POLST Form (pdf) can be downloaded below.

[download_id=”960″]

In order for the POLST to be effective as a DNR order, you must complete the identification at the top, and Sections A, D, and E. The POLST must be signed by you (or your agent or surrogate), a witness, and the authorized medical practitioner.

What color is my DNR?

It is recommended that the POLST Form be printed on Bright Pink or Bright Orange paper, so that it can be easily spotted by the paramedics in an emergency situation.

Remember that the DNR/POLST is the only document that can stop the paramedics from performing an unwanted or unnecessary CPR. The DNR/POLST must be easy to find, and easy to identify.

Some recommend tacking it to the front door of your home, or placing it on your refrigerator. If you’re worried about privacy, you might try placing it in an obvious spot in a brightly colored envelope that is clearly marked “DNR/POLST”.

Legally speaking, a DNR or POLST Form can be on any color paper, including white. A photocopy of a completed one is also valid.

How do I decide if I want (or don’t want) CPR?

Deciding about CPR can be a complicated personal and medical decision. There are many factors that come into play. As they say, “It depends.”

The first question regarding any medical procedure is what do you expect the best result will be? In the best case, how much of my current health and life-style will be restored or maintained?

The next question: What is the likelihood that the best outcome is the probable outcome?

The absolute best that CPR can achieve is that you’re the same as you were before your heart stopped.

But is that the probable outcome? CPR will likely introduce new problems, on top of any existing problems that you have. These problems may be relatively short-term, like a broken rib or two. Or these problems may be long-term brain damage.

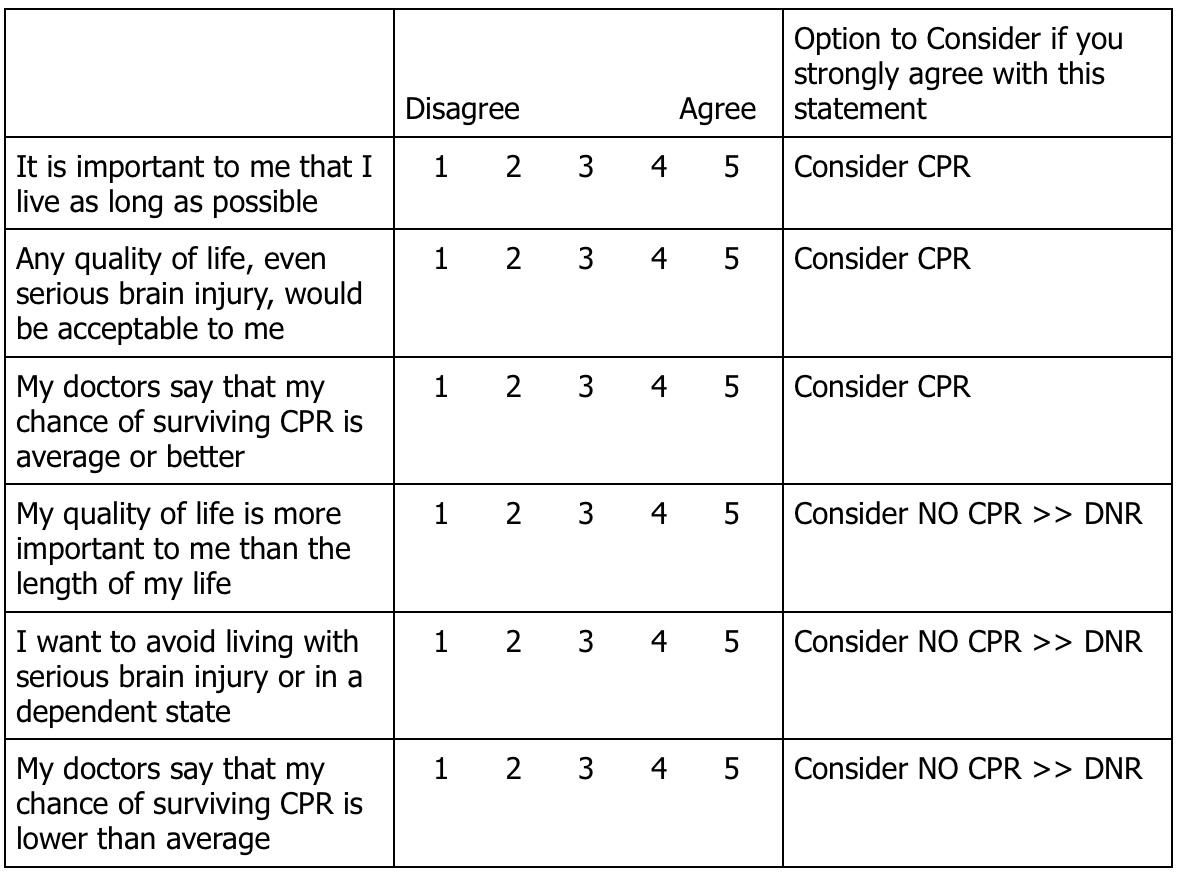

The following decision aid was developed by the Palliative Care Team at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Whatcom County, Washington. It’s a starting point – there are no wrong answers.

It’s a difficult set of factors and outcomes to balance. The best way to determine whether a DNR order is right for you is to have serious discussion with your family and your doctor (or medical advisor) regarding your health and physical condition, the likely outcomes of CPR, and your thoughts about life-sustaining treatments and death.

Additional Information

Categories: Advance Care Directives

Inherited IRAs Need Protection Is it Time to Review Your Estate Plan?

Contact John

30+ Years Experience.

Personal Planning.

Plain English.

Committed to simplifying your estate planning. Let's work together to achieve your

peace of mind.

John Varde, Attorney

180 North LaSalle, Suite 2650

Chicago, Illinois 60601

Get Started Today

If you’re ready to take the next step, download the free Confidential Estate Planning Questionnaire